Miss Saigon Sings of Dreams but Stirs Debate

- Closing Night

- Aug 30, 2025

- 19 min read

Updated: Oct 5, 2025

A multiracial production almost loses its two leading stars when it comes to Broadway.

A little over a month ago, the Broadway community was locked in a contentious debate over racial casting, this time concerning the musical Maybe Happy Ending. When a white actor was announced to take over the lead role from Darren Criss, it reignited a decades-old conversation about representation and opportunity. Long-standing Asian American figures in theater, like playwright David Henry Hwang and actor B.D. Wong, spoke out, arguing that it echoed a painful history of exclusion they both experienced firsthand.

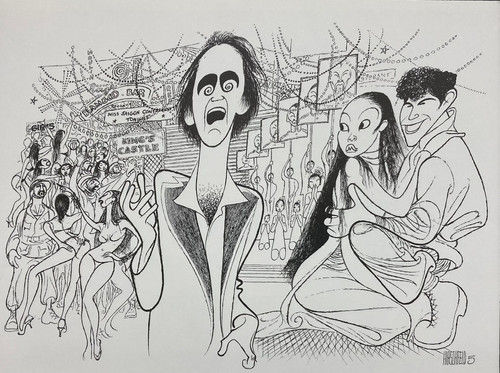

In 1990, both men spoke out about another casting scandal that rocked the Broadway community. And in response, Hwang wrote a sharp, satirical play called Face Value, which starred B.D. Wong and unfortunately closed during previews. But before I discuss that production and to truly appreciate the complex commentary this play was trying to make, we have to go back to the mega-musical that inspired it: Miss Saigon.

The anticipation for Miss Saigon on Broadway was massive. It was the new epic production from the creative team behind Les Misérables—it had spectacle, romance, and a helicopter. It was breaking box office records in London, and producer Cameron Mackintosh fully expected the same welcome on Broadway. But before the curtain could even rise, the show slammed into a colossal controversy.

And at its center was Jonathan Pryce, a British actor cast to play a Eurasian character. This blockbuster musical was suddenly being overshadowed by something far more contentious: the messy politics of casting and a raw debate over who should play what roles. Here is Hwang talking about the reaction in New York:

“It became kind of the first big yellowface protest in American theater history. East West Players, Pan Asian here in New York, Asian American theater companies, these institutions existed already to coordinate a response…But it jump started a conversation which had never been really considered before.”

According to Mackintosh, however, Pryce was the single best actor for the role and therefore artistically essential. But the stage union, Actors’ Equity Association, thought differently and refused to let Pryce take on what they saw as an Asian role. The dispute quickly grew beyond just one actor, becoming a theater-wide debate on artistic freedom versus representation. The most dramatic moment came when Mackintosh stood his ground, issuing a shocking ultimatum: if Pryce couldn't be in the show, he would cancel the entire multi-million dollar production.

Welcome to Season Two of Closing Night, a theater history podcast that dives into the stories of Broadway's famous and forgotten shows that closed too soon. I'm Patrick Oliver Jones, an actor and producer based in New York City, and this season I'll be your guide as we uncover the mysteries of productions that never even made it to opening night. Whether they closed out of town or during previews, you'll hear firsthand from those involved, revealing just how unpredictable—and unforgiving—the path to Broadway can be.

LONDON SUCCESS

In 1985, composer Claude-Michel Schönberg and lyricist Alain Boublil took the world by storm with their musical Les Misérables. After its massive success on the West End and on Broadway, the pressure was on to create a follow-up. They talked about the source of their inspiration on Theater Talk in 2017:

BOUBLIL: “The original idea is when Claude—of doing Miss Saigon—when Claude-Michel saw that picture of this mother handing her daughter at the airport, at Saigon airport…”

SCHÖNBERG: “It was exactly at the time we were transferring Les Misérables from the original run through in London, the Barbican Centre to the Palace Theater in the West End. And we were starting to think about a new musical. I was pestering Alain, why don't we do Madame Butterfly in Granada? When the Americans did invade Granada with the French in the Vietnam. And suddenly I saw this picture and I said, but the sacrifice of this woman is the same as the one undergone by Cho Cho San in the opera work. So why don't we do it during the Vietnam War?”

So they began conceiving a love story similar to Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly, but this time set during the last days of the Vietnam War. The musical focuses on the tragic romance of Kim, a young Vietnamese woman, and Chris, an American GI. All under the watchful eye the Engineer, a cunning hustler who schemes for survival and dreams of escaping to America. And as they were writing, Schönberg and Boublil even went to a local Vietnamese restaurant in Paris and asked a waitress about their use of various Vietnamese words and phrases.

When it came to casting, producer Cameron Mackintosh insisted on authenticity by casting Asian actresses as the Vietnamese women. For example, they conducted international casting calls of almost 1000 girls before deciding on 18-year-old Lea Salonga from the Philippines for the lead role. They also found male actors as well in these auditions, even ones who had no experience in musicals, like Jon Jon Briones.

“In 1988, this friend told me, 'Do you want to earn a few bucks? We're going to facilitate an audition in Manila for this Broadway producer. His name is Cameron Mackintosh. He produced Cats, Les Mis, Phantom.' What are those? I had no idea. And finally I said, might as well audition. Cameron maybe chose me because I looked like I was 12 back in those days. So they were probably thinking, oh, we need a street urchin. From there, they flew us all to London. That was my first time outside the country, first time leaving the country, first time speaking English. That was hard.”

But not all the males roles were cast with Asian actors. To add a celebrity name to the show, they chose Welsh stage and screen actor Jonathan Pryce to play the Engineer, who is described as Eurasian—half-French and half-Vietnamese. To look convincing in the part, Pryce, like other white actors playing Vietnamese in the show, wore bronzer to darken his skin and prosthetics to alter his eyes, as he explained on a British talk show in 1989:

“Prosthetics. It's a light, sort of very light latex, which is a false lid…I’d rather be without them, but they're actually, they're quite comfortable. And the great thing about them, no acting required. Once you've got those on, you just stand there and it all happens.”

When Miss Saigon opened in London in 1989, audiences loved it. Lea Salonga was praised for her voice and passionate portrayal, while Pryce was generally hailed as charismatic and commanding. Yet among the glowing reviews, no one seemed to push back on how the Asian characters were being portrayed, whether by Asian or non-Asian actors. The smash hit musical was nominated for four Olivier Awards, only winning two of them—one for Salonga and the other for Pryce. Here's Briones talking about what it was like watching Jonathan Pryce perform:

“Back in 1989, when we were rehearsing, I was just watching in awe of Jonathan Pryce. He was like this huge icon that you go, ‘I can never be like that.’”

COMING TO BROADWAY

On opening night in London, Mackintosh promised that if Miss Saigon was a hit, he’d take it to Broadway. And in 1990, he kept that promise, announcing the show would open the following spring at the Broadway Theatre. The announcement came after months of back-and-forth between the Shubert and Nederlander organizations, Broadway’s two biggest landlords, who both wanted bragging rights to the hit production. Shubert won out, which ironically meant Schönberg and Boublil’s other musical, Les Misérables, would have to eventually move to the Imperial after a three-year run at the Broadway.

With a budget of $10 million, Miss Saigon was officially going to be the most expensive production in Broadway history at that point. In today’s dollars, that’s about $25 million, which has actually become a standard figure for big Broadway musicals in recent seasons. To pay for his record-breaking budget, Mackintosh went with record-breaking ticket prices as well, charging $100 for the most coveted seats in theater, the front mezzanine. While these first-ever $100 seats caused a stir among critics and theatergoers, the show's biggest battle was yet to come.

EQUITY TAKES A STAND

When it was announced that Pryce would transfer with the production to Broadway, the stage union Actors’ Equity immediately condemned the casting. And after a meeting with Mackintosh and advocates for and against the casting, Alan Eisenberg, Equity's executive secretary, released a statement in July 1990:

“Equity believes the casting of Mr. Pryce as a Eurasian to be especially insensitive and an affront to the Asian community…Council’s feeling in no way reflects on Mr. Pryce, whose work Equity admires and honors. But that is not the issue.”

Equity’s president, Colleen Dewhurst, echoed the sentiment by saying, “It would be an unconscionable step backward to allow this casting to go unchallenged.” And Equity was not alone. Asian American performers and organizations rallied quickly. Tony Award winner BD Wong, whose breakout role in M. Butterfly just two years earlier had made him one of the few visible Asian actors on Broadway, minced no words: “The casting of Jonathan Pryce is a reminder that we are dispensable. That we are not allowed to play ourselves, even when the role is written for us.” Jon Jon Briones echoes this sentiment:

“Because growing up in the Philippines and watching those Hollywood movies, we got used to white people doing yellowface and doing prosthetics and, you know, and doing an accent. So when we were doing Miss Saigon in London, never, you know, I didn't even think twice about that. And then when that happened, that uproar, I began to think. I went, 'Yeah, that makes sense.’ That was like a wake up call for everyone.”

In response, Mackintosh released his own statement, firing back at Equity for “totally disregarding the rights and needs of Miss Saigon’s creative team.” He noted that the show’s casting director, Vincent Liff, held auditions in Hawaii and in six cities with significant Asian populations as well as seeing 750 Asian performers in New York in order to cast the show’s 34 non-Caucasian roles. He also questioned why the union was singling out this one particular role, pointing out that if Jonathan Pryce were an American instead of a Brit, Equity would not have objected. As far as he was concerned, the situation was “utter nonsense” and accused the union of backtracking on earlier assurances that Pryce would be recognized as a star and therefore allowed to perform on Broadway. He went on to say:

“The hypocritical policy which Equity has adopted will make it impossible for us to work on this production if the present climate on Broadway continues…Unless Equity changes its position within the next two weeks, I will have no choice but to withdraw the production.”

Now, Mackintosh threatening to cancel his show was a big and bold move for a producer, especially considering that Miss Saigon had already brought in a record-breaking $25 million in advance ticket sales. However, this was not the first time Equity and Mackintosh had argued about casting. British theater critic Sheridan Morley explains how the same thing happened with his production of Phantom of the Opera just three years earlier:

“Cameron Mackintosh has remembered that Andrew Lloyd Webber, in this same situation with Sarah Brightman two years ago, when, with a rather better case, Equity was saying, 'In America we can find an American girl to play this part.' Andrew said, 'No Sarah Brightman, no show.' And Equity sure enough came back and said, 'We think we need the show.' Because huge numbers of their members will now complain to American Equity that they have been denied work because of the Asian lobby.”

However, Tisa Chang, the artistic producing director of the Pan-Asian Repertory Theater in New York, called Mackintosh's cancelation threat “a lot of hot air,” adding that “when there is money to be made, he will make it.”

BROADWAY MISSES SAIGON

Two weeks after Equity condemned the casting of Jonathan Pryce, they took a formal vote and denied him permission to join the New York production. That’s when Mackintosh followed through on his threat. He canceled Miss Saigon on Broadway, rather taking it to arbitration, and leveled accusations of “reverse discrimination” at the union. He called their stance "a disturbing violation of the principles of artistic integrity and freedom,” and stated he would not open the show in New York unless Jonathan Pryce was with it.

The move was seen by some as a matter of principle, and by others as a publicity stunt designed to frame the union as a group of meddling censors. Within days, newspaper headlines screamed about the "death of Broadway's biggest hit." Pryce, who was still playing the role over in the London production, had this to say when he heard the news:

“I was shocked and I still am kind of numb about it, really. It's a decision we didn't expect them to make. We thought, I especially thought that logic and reason would see through, because what they've come through with as an argument seems to be quite illogical. And I don't know if any changes can be made now, but once the shock has worn off, I think I'm going to feel pretty angry about it.”

But if Equity thought it would win broad support, they miscalculated. Reaction within the theatrical community was mixed but heated. Frank Rich of the NY Times sharply criticized the union for prioritizing politics over talent:

“A producer’s job is to present the best show he can, and Mr. Pryce’s performance is both the artistic crux of this musical and the best antidote to its more bloated excesses. It’s hard to imagine another actor, white or Asian, topping the originator of this quirky role. Why open on Broadway with second best, regardless of race or creed? … The barring of Mr. Pryce is insupportable on every level. By refusing to permit a white actor to play a Eurasian role, Equity makes a mockery of the hard-won principles of non-traditional casting and practices a hypocritical reverse racism.”

The Nontraditional Casting Project also agreed. They were a nonprofit organization founded to promote non-discriminatory casting in theater, and saw “no reasonable basis” to oppose Pryce’s casting. While its board members, which included actor James Earl Jones, fully acknowledged the concerns of Asian actors about discrimination, they also emphasized Mackintosh’s pledge for open, unbiased auditions to ensure Asian and other minority actors would be considered for understudies, replacements, and future productions.

At the same time, not everyone at the Project agreed. Board member Abel Lopez applauded Equity’s stance, hoping it would signal a tougher approach to productions across America. Even British Actors Equity offered sympathy for the American Equity position, but nonetheless sided with Pryce:

“We can understand their desire to help their Asian members. Actors have a rotten time. All actors everywhere, and particularly here and in America, and minority groups of actors have a worse time than ordinary actors, obviously, What we object to, and object to quite strongly, is that they aren't applying those policies to their own members. They're using the coincidence of Jonathan Pryce and Miss Saigon going to Broadway to apply their new policies, try them out on him, and that we consider to be offensive.”

Casting director Vincent Liff defended his actions on the same grounds, saying that if there were an Asian actor with Pryce’s background and reputation, he would have certainly discovered him by now.

THE POLITICAL BECOMES PERSONAL

Still, there were many who sided with Equity, seeing the union's stance as a long-overdue push for diversity. Sylvie Drake of the Los Angeles Times described Pryce’s portrayal as “a grotesque caricature of an Asian.” For her, the issue was about fidelity to the text and honesty in the storytelling. As she pointed out, if the creators bothered to specify the Engineer’s mixed heritage, then to cast a white actor in the role wasn’t creative license—it was a contradiction that erased the very foundation of the character.

For Asian American performers, though, the debate was more than an abstract discussion of context and authorship. It was personal. Tisa Chang spoke passionately about the sting of invisibility, saying: “We are here. We exist. And yet, time and again, we are told we are not good enough to play ourselves.” Wong echoed this in even sharper terms:

“When I see Jonathan Pryce putting on prosthetics to look more Asian, I see history repeating itself. I see yellowface. I see Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer. I see a white man pretending to be what I am told I cannot be.”

While Pryce did eventually stop wearing the prosthetics in London due to audience complaints, Wong’s statement crystallized the stakes for Asian American actors. This wasn’t just about one show. It was about whether Broadway would keep telling minority actors to wait their turn. Because for many, Pryce’s casting was only part of the issue. They were also standing up against orientalism, misogyny, and stereotypical portrayals of Asians on stage. And they were doing so on the streets and in front of theater building and even Actors Equity. Here’s one demonstrator explaining why she was protesting:

"And as an Asian woman, I'm scared for my safety. As a woman of color, I'm scared about the larger issues about Miss Saigon, which Lamda refuses to acknowledge. They haven't even said that was racist, sexist, or even perpetuates violence against women. And in organizations that supposedly represents everyone, why do I feel left out? Why is the Asian community left out? And since, you know who's gonna be left out next?”

EQUITY BUCKLES...AT FIRST

But following Mackintosh’s cancelation, Actors Equity found itself under immense pressure from Broadway investors and producers as well as its own members. Owners of multiple Broadway theatres even signed a petition asking Equity to reconsider. So on August 17, 1990, just ten days after their initial decision, they reversed course, granting permission for Pryce to reprise his role on Broadway. In doing so, Equity stated they had “applied an honest and moral principle in an inappropriate manner.” But by standing down, Equity effectively condoned the very thing they sought to prevent, and just tiptoeing away with its proverbial tail between its legs. While they framed the reversal as a pragmatic move, to many Asian American actors, the message was clear: Broadway’s commercial machine would always outweigh their voices.

As for Mackintosh and Pryce, they didn’t immediately celebrate the win. Both men took time to decide if they even wanted to come to Broadway. Mackintosh was concerned with the logistics and finances of restarting the Broadway transfer, while Pryce was still upset at how the union handled the controversy, wondering if he even wanted to perform after being publicly vilified. They did eventually come around, and Miss Saigon resumed its journey to New York.

However, Equity wasn’t done stirring up controversy. Just four months later, in December 1990, the union now set its sights on Lea Salonga. (Yeah, that’s right.) The issue? She was a Filipina actress, not American. And just like with Pryce, Equity wanted her role to be played an Asian American. Mackintosh, of course, stood by his star, stating that after auditioning 1,200 candidates, he found none to match her. He formally appealed to Equity, and this time around sent the matter to arbitration to be resolved.

The battle over Salonga’s casting was seen by some in New York as Equity’s attempt to get back at Mackintosh for the Pryce dispute. For those in the Philippines, though, it was viewed as another instance of American prejudice. Salonga’s father, a retired merchant marine officer, voiced his outrage, stating, "And now the American Equity is trying to keep a U.S. Navy man's granddaughter out of playing on Broadway - because she is a Filipina!" A Manila columnist, Max V. Soliven, added to the outcry by writing, "It's sad that some Americans, in a land which has long preached equality of man and equal opportunity, have become such rabid racial bigots."

Despite the international uproar, Salonga herself remained composed. Speaking to a Washington Post reporter while in Manila performing homecoming concerts. she said that it’s not the end of the world. “If Broadway does happen, then fine, it's great. If it doesn't, I'm not going to be a sourpuss.” However, she was firm about wanting to be on Broadway and showcasing her country’s musical talents. “It would mean another chance for the Filipino to get a foot in the door, and hopefully push it open all the way.”

OPENING NIGHT AND TONY AWARDS

Well, on January 7, 1991 an arbitrator helped push that door open by reversing Equity’s ruling, allowing Salonga to star on Broadway in the role she originated. Four months later, Miss Saigon opened to mostly rave reviews and ecstatic audiences, and yes, protests as well.

Protestors even got into the theater, disrupted the show, and somehow got into the fly system, threatening to drop things on actors. Order was eventually restored and opening night continued on. Despite the continued backlash, though, Miss Saigon would go on to receive 11 Tony nominations, tied for the most that year with Will Rogers Follies, which would end up winning Best Musical. However, Miss Saigon did win three awards, and each acceptance speech was a fascinating epilogue on the controversy.

First, Lea Salonga became the first Asian actress to win a Tony Award and the first to win for Best Leading Actress in a Musical. After a journey that saw her fighting to get on Broadway, her speech was a triumphant moment for a young artist and her country. Here’s what she had to say:

“This can't be for real. I remember watching these on TV when I was a little girl in Manila. And this can't be real. I'd like to, first of all, thank God for all of his blessings. I'd also like to thank Actors Equity for (laughter) for giving me the chance to come here to the United States. You guys have been so great. Like to also thank Cameron, Elaine, Claude, Michel, Richard, Nick. You guys gave me the chance to do this role, and I thank you. I also like to thank my family. My mom up in the mezzanine, my brother down here in the orchestra. Hi, guys. You guys have been most supportive. And to the entire cast and crew of Miss Saigon. You guys are the greatest people anybody could ever work with. And this also goes to everybody back home who dreams of winning a Tony. Well, I got one. And the dream can come true for someone else, too. Thanks a lot. God bless.”

The second award went to Hinton Battle, who had previously been in five Broadway shows and had already won two Tonys. In Miss Saigon, he played the role of John Thomas, a Marine and a friend to Chris.. Now, Battle is a Black actor whose part was originated by a white actor in London. So he chose to make his acceptance speech a powerful and pointed statement:

“Oh, my goodness. Oh, my goodness. You know, the first two times I was up here was because my feet were doing all the talking. And this time I get to not dance as much or dance at all. I have to thank the producers, Karen McIntosh and the Shubert Organization and the creative staff and creative people of Miss Saigon for giving me the opportunity to come to Broadway doing something other than dancing and singing. I only sing this time and I act this time. And I have to thank you for that. Also, I'd like to thank the producers for being colored blind. I really must do this because. Because they took a chance and was daring with their casting. And it works. And I know it works because every night when I go out there and I sing the “Bui-Doi” song, and I look in the audience and I see tears in the people's eyes, I know that they're colorblind as well. And I hope this sort of casting can continue. And I have to thank the cast and everybody. Willie Falk, my God. And Leah and Jonathan Price and the crew and, oh, God, I can't even think anymore. And the American Tony Award, because this means a lot to me and I thank you from the bottom of my heart. Thank you so much.”

And lastly, Jonathan Pryce won the third and final award for Miss Saigon, taking home the trophy for Best Leading Actor. After all he had been through, his speech was notably understated and lacked the overt political commentary of his fellow cast members, instead focusing on the artistic community and his family. Here’s what he had to say:

“Thank you. Thank you very, very much. I suppose that now is the time to tell you about my new book, which is 101 Things to Do with a Used Cadillac. God, I'm shaking. Yesterday was my birthday, and I spent the morning with my children. I spent between shows with Kate, and the rest of the day, I spent with some of the nicest, most talented people you could ever want to be with. They are the and as Hinton said earlier, the multiracial cast of Miss Saigon. I thank them.”

Miss Saigon lasted for more than 4100 performances and ranks as the 15th longest-running show in Broadway history. But the debate it sparked has continue well beyond its closing night in 2003. When the show was revived for its 25th anniversary in London, both Pryce and Mackintosh reflected on the original controversy.

Pryce still defended his casting, saying that while it was a good argument to have, that original London cast was a mix of nationalities, with non-Asians playing Asians and non-Americans playing Americans, and that was "the joy of that company." He felt that America just didn’t recognize that. “If the argument is valid that any actor of any race should be able to play any role, then it is a two-way traffic. But I am all for supporting the fact that more opportunities need to be made for non-white actors."

On the other hand, Mackintosh admitted that the casting of Pryce was his "biggest mistake." He told the Telegraph he had called the controversy "a storm in an Oriental tea-cup," but now says he was “actually being stupid." He now accepts that those who argued the character should be played by an actor of Asian descent had a valid point.

The Miss Saigon saga remains instructive precisely because it was so messy, so human. There were no pure heroes, no villains without a defense. This wasn't a debate between good and evil, but a clash of sincerely held beliefs: a producer’s right to artistic integrity, a union’s duty to its members, and a community’s call for justice. In the end, all sides found a way forward, proving that even the most intractable debates can lead to an uneasy peace. The show went on, but the questions it raised about who gets to tell whose story were just beginning.

Closing Night is a production of WINMI Media, with me, Patrick Oliver Jones, as writer and executive producer. Blake Stadnik created the theme music. And Dan Delgado is editor and co-producer not only for this podcast but also for his own movie podcast called The Industry. Much appreciation goes to the following resources listed below. And be sure to check out the next episode all about Face Value and its journey to closing night.

Bonus Clip - THEATER TALK 2017 (March 25, 2017)

MICHAEL RIEDEL: Cameron canceled the show for Broadway. Were you guys—?

CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG: Postponed the show?

RIEDEL: Were you guys in favor of his decision or were you terrified?

ALAIN BOUBLIL: Well, we were terrified by the fact that he was refunding $33 million, if I remember well. And that we would normally have a little slice of that.

SCHÖNBERG: But I must say we knew that one day it will come, Right?

SUSAN HASKINS: Yes, right.

SCHÖNBERG: What we were terrified is that suddenly the show was not the show we have been writing. Because we never write a show to have controversy about the casting of somebody who was supposed to be half Asian, half European. Because in the opera work, the character of Goro is the go between. He's Asian, but dress with a Western.

RIEDEL: With a Western costume, yeah.

SCHÖNBERG: Costume. So we wanted the same for the Engineer. A kind of half Vietnamese, half. So it turns out that he is Asian.

BOUBLIL: And even more than that, we didn't know what the word “blind-casting” meant. We discovered the existence of problem. And since then we have become the biggest employer of—of blind casting artists.

HASKINS: Yes. With the world.

RIEDEL: That's the irony of Saigon—of Asian performers all over the world have been given ton of work from this.

HASKINS: Including, and the name of the Asian actor now who plays the Engineer is—

BOUBLIL: Jon Jon Briones.

Sources and materials used to create this episode...

General Info

Roundabout Theatre, The Guardian, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, AMERICAN THEATRE, Teen Vogue

Timeline History

https://www.nytimes.com/1990/03/02/theater/miss-saigon-finds-home-on-broadway.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/26/theater/actors-equity-attacks-casting-of-miss-saigon.html

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-08-09-ca-562-story.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/10/theater/jonathan-pryce-miss-saigon-and-equity-s-decision.html

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-08-20-ca-835-story.html

https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/19910101/1258381/lea-salonga-she-accepts-saigon-fuss

https://socialism.com/fs-article/miss-saigon-money-calls-a-racist-tune/

Video Sources

Making of Miss Saigon - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZKjLjUh0OQ (Pryce Engineer 57:06) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RWOxbeNcTdU (6:22)

1989 London Cast excerpts - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JOJCgegMcUg

1989 British talk show - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hl6jv-_a_Ig

Thames News - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=thREx1uSqrE

Protests - https://vimeo.com/998757547/d9060c54ef

1991 Tony Awards performance - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YpWcQQQkLM (Jeremy Iron Intro)

Salonga Tony Speech - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y6CA9jGjQmo

Pryce Tony Speech - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hxk_np4Qw84

Battle Tony speech - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IP0ZhK7BUEE

Theater Talk 2017 - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79rPwnafzhk

Reviews and Commentary

Variety review - https://variety.com/1991/legit/reviews/miss-saigon-1200429084/

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-04-13-ca-326-story.html

Miss Saigon Legacy (PBS SoCal) - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXsuTsiJiBQ

War on Representation - https://humcorestories.wordpress.com/2014/06/19/miss-saigon-the-war-on-representation/

Better Late Than Never - https://adventuresinvertigo.blogspot.com/2015/09/miss-saigon-better-late-than-never.html

Mackintosh 25 yrs later - https://www.broadwayworld.com/article/Cameron-Mackintosh-Regrets-1991-Yellow-Face-MISS-SAIGON-Casting-20140521

Pryce 25 yrs later - https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/jonathan-pryce-on-the-controversy-that-almost-sunk-miss-saigon-20160926-groc7a.html

Comments